Why Would You Want to Live on An Island?

For me, the answer to the question of 'Why Martha's Vineyard?' lies in my heart, not in my head.

“We were never cast out of Eden. We merely turned from it and shut our eyes. To return and be welcomed, cleansed and redeemed, we are only obliged to look.”

— Margaret Renkl, The Comfort of Crows

Maybe this place picked me,

waited for me all these

forty-five years, waited for me

to name my madness, claim

my art, welcome the truth

of imperfection. To come back

home, the price of a ferry ticket

to find my soul.

— Susie, February 2008

She asked the question with no judgment, I really believe.

Did I hear her say, “Who would want to live on an Island?” No. Did I hear her say “Why would you want to live on an Island?” Not really. Did I hear her say, “What made you want to live on an Island?” Yes, I think that’s what I heard, what she meant. Though the words came out slightly differently when she posed the question to both my husband and me on a few separate occasions.

She – this houseguest, a person whom we love – followed the question by acknowledging the allure of beauty and beach, while betraying some incredulity at our tolerance for inconvenience. I could see the machinations of her brain reflected in the puzzled look on her face when she queried us. Slowly it dawned on me that she was actually posing the question to herself: How would she feel about living year-round in a place seven miles out to sea (with no malls, no fast food, no Starbucks, no stoplights … no easy access to family)? She had been observing our life and wondering what it would be like to inhabit it. She let her imagination go there, but ultimately (to paraphrase Daniel1) the Island was weighed in the balance and found wanting.

That settled, she was still genuinely interested in why we came here, why we stay here.

I do not have an elevator speech. I feel self-conscious and a bit awkward articulating the profound effect this place has had on me – how it reconnected me to the natural world and fueled my spiritual growth. I’ve written about what I define as My Vineyard, but it is not an easily digestible soundbite.

So I prevaricated in my answer, reeling off a list of benefits: a tight-knit community of interesting people with similar values (self-reliance, generosity, a lack of pretense, a love for the land); the joy of living without malls and fast food and super highways; the simplicity of fewer choices; the proximity to so many farms, the opportunity to eat so much locally grown food.

And:

The clear night sky, lacking light pollution. The cocoon of morning fog. The extravagance of birds and the luxury of quiet. The oxen. The otters. The lambs in late winter, the calves in summer. The Fair. The Cliffs. The Chappy ferry. Pizza night at the Orange Peel Bakery, Illumination Night in the Camp Ground. Gingerbread cottages. Brick sidewalks. The Arboretum. The Gay Head Light. Cedar Tree Neck and Waskosim’s Rock. Wampum. Bay scallops. Sea glass. Beach plums. That Menemsha sunset. This list could go on and on.

I told her about our anachronistic small-town existence, where we are on a first name basis with the postmaster, the pharmacist, the grocery store manager, the gas station attendant, the pastor, the Rabbi, the librarian, the fishmonger. Where we literally never go out in public without seeing someone we know. Two degrees of separation between everyone.

What I didn’t say was how this kind of casual social interaction is reassuring and comforting to me. I’m not a person who loves big crowds or big parties or intense social activities, especially in sobriety. (I actually never did, but I faked it.) So I appreciate the small bits of conversation and connection I can have just by going to the post office.

The languid pace of (off-season) Island living also suits my sobriety. I grew up in a city. Did my New York thing, danced at Studio 54, ate at Elaine’s. Did the high-pressure job. Did a bunch of TV appearances. Spent 17 excruciating minutes in front of the camera with Martha Stewart.

And I don’t honestly think I could do any of that now and maintain serenity. Like many alcoholics, I’m a recovering perfectionist with an overdeveloped sense of responsibility (a childhood survival tactic of course), and it is difficult for me not to do all the things put in front of me, and with diligence. It’s not that I don’t work hard at my current job, which includes meeting non-negotiable weekly deadlines, or that I don’t stand up and speak in front of a crowd of people when I’m asked to.

But my Island life affords me time outside every day, and that is how I maintain my well-being.

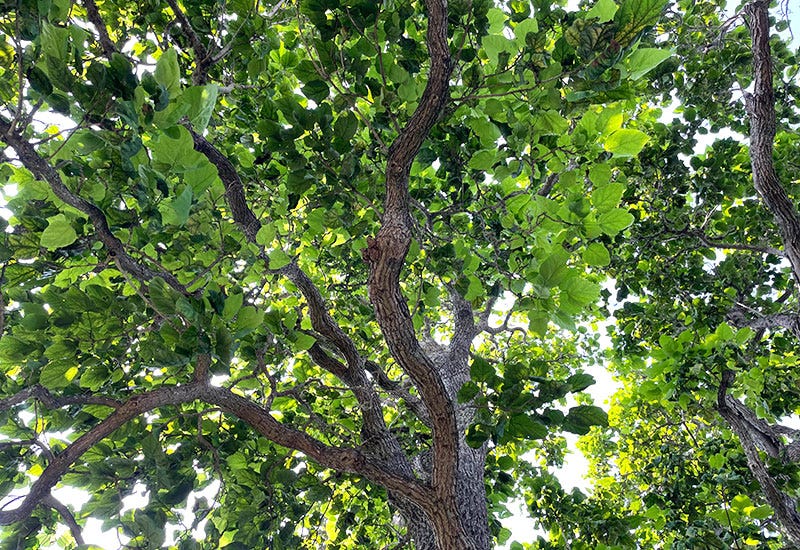

Every single day my feet are in contact with the earth: the rich, dark, composty soil of the woods, soft beds of pine needles, bouncy pillows of moss, the brittle, scratchy field grasses and the squish of rain-fueled muck.

Every day I feel the wind – that constant, relentless wind – tap me on the shoulder and say, “I’m here.” It tickles the back of my neck, seeps through my down vest, stings my eyes.

Every evening I step into the path of the last rays of sunlight as they bubble across the hayfield towards me, bouncing off the hedgerows and bursting against my face, leaving a residue of warmth and glow.

A day never goes by that I don’t cross paths with a rabbit, a skunk, a deer, a turkey, or a crow. Often they stop, unafraid, and we stare at each other, wondering.

To my houseguest I throw out the fact that there are 100 walking trails on the Island. And that I would feel safe walking anywhere alone. What I don’t describe to her is the fear I felt the first time I walked through Menemsha Hills, descending on a winding path through thickets of naked, gnarled tree branches to a destination that seemed elusive. I was afraid of the woods, afraid of the thoughts in my head, afraid of uncertainty.

And I don’t describe to her the clearing I reached in a different wood on a different walk many months later, where I sat still, and like Wendell Berry’s narrator in The Peace of Wild Things, came into a place of acceptance and strength and a genuine feeling of being at home.

If I were being straight with my houseguest, I would say this: that coming to the Island was like going to rehab for me, though I didn’t know it on the cold and stormy night in January of 2008 when I boarded the ferry and weathered the rough crossing huddled in my car, crying. I guess I’m just the kind of person who has to stay in rehab for a long time, because I’m still here. And this is where I found my serenity. And this is where I’ve made the connection between my own inner strength and the power of a spirit that dwells in nature.

I may have come here using the alcoholic’s favorite evasive tactic, known as “doing a geographic” (they generally don’t work since wherever you go, there you are), but I lucked out. Or, as I believe now, there was a plan afoot for me. Because I landed in the place that laid out a path I could follow to find myself. Somewhere between that first tiny vegetable garden I planted on the Island years ago and the dahlias I dug out of the ground today lies my lifeline.

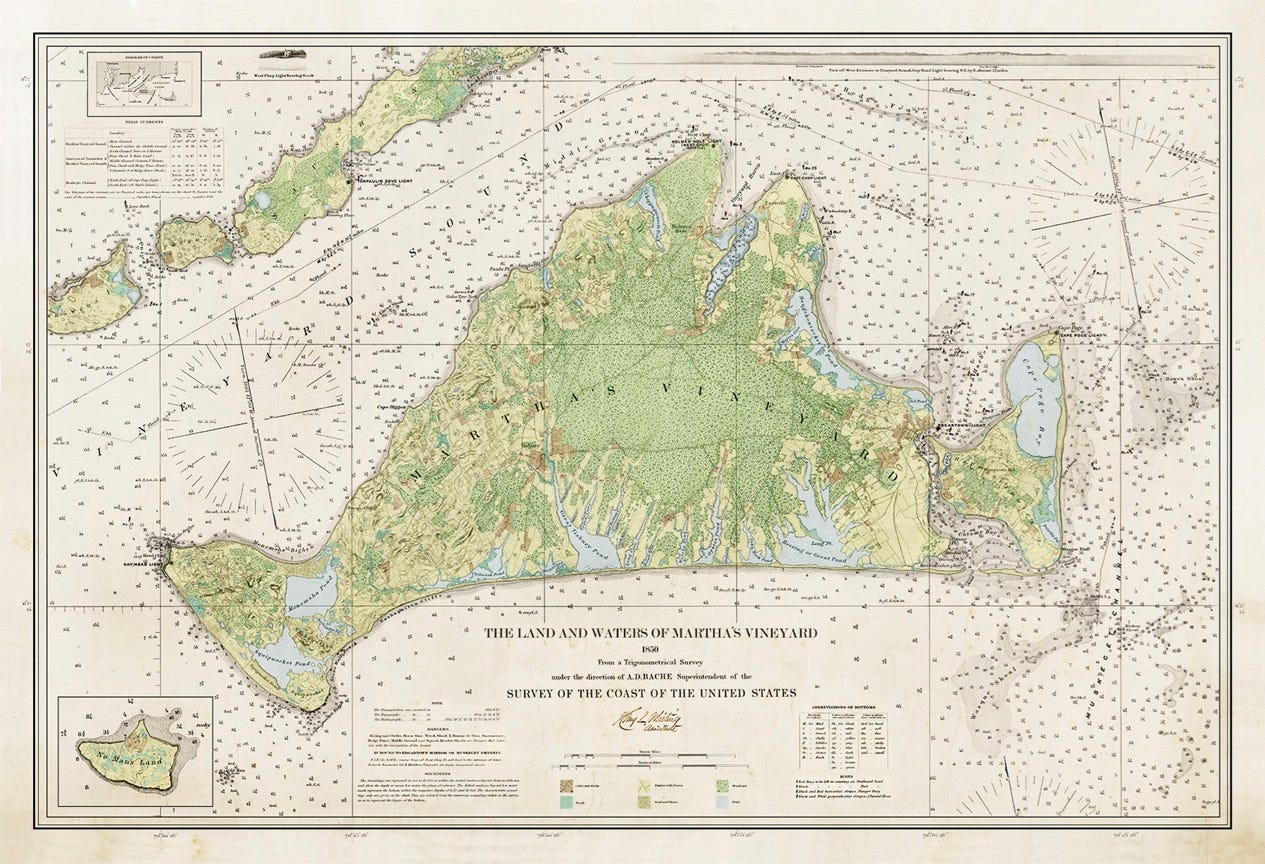

There is one last thing I mention to our guest, pointing to the Henry L. Whiting 1850 survey map of Martha’s Vineyard on our wall. I am fascinated by the history of this place, I say out loud. From the glacial moraine that formed the Vineyard to the food-rich ponds and forests that sustained the earliest Wampanoags, to the 200-year-old cart paths and ancient ways that we still use to traverse the Island.

Because 40 percent of Island land is in conservation, there are landscapes everywhere unaltered by modern structures. If I squint (and I don’t admit this), I can imagine that I’m living here 50, 100, or 150 years ago. The deceptive romance of that notion – that somehow life was even simpler then, before the Island became a popular summer resort – is something I acknowledge. And yet I keep the fantasy close, for my own sake.

To be perfectly candid, I am the kind of person who finds a certain romantic appeal in boarding a boat to come home and in living on a place surrounded by water with no bridge. Do I, like many of my fellow Vineyarders, value being “away” from the mainland? Yes.

It is not easy to find your comfort zone in this life, or to acknowledge what you need to survive. But it is worth the search, even if it is hard to describe what you’ve got when you get there.

The Book of Daniel 5:27

We get the same question out here in Montana, especially about our cabin, 40 minutes south of town, 20 minutes from the nearest gas station/mini grocery.

Because I didn't like all that other stuff, and while I didn't succumb to the family alcohol disease, I did always feel uneasy in my skin, and lonely. Like you, I rely on the safety net of low-key social interaction. Here's to those of us who took a step sideways.

Needed this today, this week. The time change is hardest for me here and going into my third year of living here year round I keep questioning myself on why do I live here. I'm a city person to my core.... or so I thought. Living here may be inconvenient but the rewards of small conversations in the post office or grabbing coffee, the circle of friends that continues to grow at a good clip, for me, my family being here... the list goes on makes me comfortable here. Sure, there are some pretty significant challenges like not seeing my grandkids in real life for months at a time and again, I can't not bring up the darkness again but I feel like I'm year three I am really settling into this life and understanding how wools come here for a spell, blink and realize they have been here 20+ years. This year it's my turn to accept and settle if not completely lean in to this inconvenient dark bit completely rewarding life on MV.