“We are the storytelling species. We make art to metabolize and clarify experience, to find the truth, to make meaning.”

— Elissa Altman, Permission

I have been reading my friend

’s new book, Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create. It is proving revelatory.My brain has been short-circuiting, with memories untethering from the moorings I had tied them to and realigning into new truths. I am finally coming to understand some of the roadblocks that keep me from committing to writing a memoir. Fear and shame – and the voice of my mother – are definitely on that list. But there is more.

Though I knew what the subject of Elissa’s book was (I even took a class from her last fall!), I was not prepared for how personally affecting it would be. Permission is unique in that it is part memoir and part memoir-writing master class. But the story and the methodology for writing such a story are knit together so seamlessly that the reader is drawn gently but firmly into introspection (not to mention underlining and note-taking) in what I might call a safe zone. Permission actually gives you permission to begin thinking about your story in a different light, even before you pick up a pen (or tell your story with some other art form).

Of course, the end goal of Permission is to bring you to a place where you’ve vanquished the fear, quieted the voices (at least somewhat), and mustered the courage to write your story as you experienced it. Equally important, Elissa advises, is to examine your motives for writing, to assess your tolerance for risk, and to exercise compassion for the actors (even the bad ones) in your story:

“Writing about others must have its roots in the search for truth and clarity, and that search needs to be made – even when there is enmity between the narrator and her characters – with empathy.”

Elissa’s personal story in Permission is about intergenerational trauma – specifically how the actions (one particular action) of her paternal grandmother affected her father, who ruminated on the memory of it in such a way that it infused the entirety of his only daughter’s childhood.

Elissa and I share grandmother troubles, so her story is particularly resonant with me. And while I have, in the past, understood what intergenerational trauma was, I had never really pushed myself to consider how broadly it can manifest.

In Permission, Elissa cites Marianne Hirsch, the author of The Generation of Postmemory, who coined the term “postmemory” to define “the relationship that the generation after bears to personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before – to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images and behaviors among which they grew up.

In her book, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Hirsch defines the idea of postmemory in this way:

Postmemory characterizes the experiences of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation shaped by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.

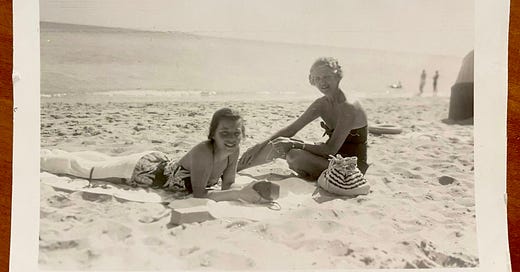

I have written a little about my maternal grandmother’s alcoholism and her tragic death. I have alluded to the anxiety that my grandmother’s condition created for my mother, who, after her two older sisters left home, bore the burden of hiding the family secret, while her father’s attention was constantly diverted elsewhere. (He was a busy surgeon.)

I’ve never mentioned that my grandmother’s father was also an alcoholic, and such an unpleasant man that my grandmother left her small town quickly and eagerly and tried never to look back. She became a nurse, married the handsome doctor and had three children, participated in a seemingly grand life in a big stone house with beautiful gardens in the nation’s capitol, chaired the garden club and won praise for her flower arrangements. All while battling a terrible disease that would take her down, and for which there was a crushing cultural taboo against acknowledging and treating.

Once, a few years after my (own) mother died, I asked my father what my grandmother had been like (she died when I was 2½). The first thing he said was, “She was sad.”

In a pattern that I would later repeat in my first marriage, my mother married a man (my father) whose father was an alcoholic. (My first husband and I both had alcoholic grandmothers who died too young and tragically, as well as other alcoholic family members.) I don’t have any studies to back me up on this, but I think that the familiarity, even unspoken, of family trauma, can bind people together, and I think my parents found safety in each other.

The burden of my grandfather’s affliction that my father bore – as did all of his brothers in different ways – was intense. My grandfather, whose grandfather had also been an alcoholic and died early, didn’t start drinking until he was 40, a good while after he had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, become an officer and an engineer, married, had six sons, left the Navy, and faced the responsibility of caring for a household of 10 during the Depression with little money. Yet the disease was there waiting for him.

But for many reasons, the trauma my father faced did not carry over and affect me and my sister the same way my mother’s life-long anxiety did. Partly this was because my Dad was better at hiding his. Partly it was because my mother had so much control over our day-to-day lives. But mostly it was because my mother’s anxiety was so palpable.

I have known for many years that my mother’s anxiety, my relationship with my mother, her relationship to my sister, and the anxiety I inherited from her – is the story of my life. My story is not that I became an alcoholic; it’s not that I married (the first time) for the wrong reasons; it’s not that I wound up not having children; it’s not that I couldn’t or wouldn’t progress beyond a certain point in my career. Nor is it that I did well in school, made friends easily, talked myself into leadership positions, became a writer and an editor and a farmer, wrote books, developed a spiritual life. It’s not the bad stuff or the good stuff. It is my mother.

It occurred to me the other day how your life story begins even before you emerge from the womb. There are chapters written for you by genes and circumstances and planetary alignment.

But in reading Permission, I’ve begun to think beyond my mother. It occurred to me the other day how your life story begins even before you emerge from the womb. (Hence, postmemory). There are chapters written for you by genes and circumstances and planetary alignment. And on the night that you are born, and the days and weeks after, more chapters are written for you before you can even speak.

For the first time, I understand that stalling out on the memoir isn’t just about hearing my mother’s voice in my head, or not wanting to hurt my father. It’s wanting to avoid certain circumstances that defined my early life (and always will, in some ways) that I had no control over. Circumstances that I feel shame and embarrassment and confusion about. (Confusion because sometimes pride and shame mix together.)

If you’ve read this far or know anything about me, you can probably guess what some of my discomfort is about: affluence and privilege.

The truth is that I can’t write about my childhood, about my life at all, if I don’t reference where I came from and how thoroughly I was indoctrinated with family culture.

These are words, linked in my mind like a refrain, oft-repeated to me as a child:

You are a fourth-generation Washingtonian. You are the grandchild of a prominent surgeon, chief surgeon of three Washington hospitals. You are the descendent of a signer of the Declaration of Independence and many other statesmen. Your family has been in this country for 375 years.

Try to unpack that without flinching.

Or this:

A few years ago, I discovered that the hospital I was born in – Columbia Hospital for Women – was (still) segregated in 1962. That means my mother gave birth on a different floor from women of color (no doubt in somewhat more comfortable and private quarters). I was horrified to learn this. (I subsequently learned that Columbia had, at least, from its inception in 1866, always treated women of color, while other hospitals in the 19th century and even later, turned them away.)

I was taken home to a tidy white brick house on a tree-lined street in a neighborhood where only white people lived, because (I now know) of Washington’s long history of red-lining, steering, covenant restrictions, and discrimination by realtors. In poking around, I also learned that I was taken to an amusement park (by friends of my parents, more than once) that did not admit people of color at all.

My parents were not bigots, but they inherited the social order their parents lived by, and in both their childhoods AND MINE, white people lived on one side of town, people of color lived on the other. Until I was in high school, my primary interaction with a Black person was with Agnes Smith, our housekeeper. I remember vividly that Agnes traveled a long way to get to us from southeast Washington, changing buses frequently, and then turned around at the end of the day to do that trip back. Agnes worked for other families in our neighborhood, but when she died, I remember that my mother and I were the only white people at her funeral.

When I got to college (a southern university) and co-majored in religion, I took a course on cults that included an in-depth look at the history of the Ku Klux Klan and the terrors it waged. It was the thing that catalyzed my lifelong obsession and anger with institutionalized racism – any racism, in fact, no matter what academic moniker you give it. It is very simple: We white folks did everything we could to repress black folks for hundreds of years.

I am not exaggerating when I say “we” white folks, because I have ancestors (and I have most definitely never written about this) who were slave owners. And some who were abolitionists, thank God. But while I didn’t choose these ancestors and couldn’t have controlled what has come down to me through many generations, I still have to carry it and hold it up to the light if I am to write the truth of my life and all that has shaped it.

There is so much to any life that lives in the shadows, and without shining a light in those dark corners we can’t tell the truth, or the whole truth. You know the Greek word for truth is aletheia, which translates as “un-hiddenness.” Disclosed. Revealed.

I am not yet finished with Permission, because I don’t want to be. In the evenings, I read a little, often reread what I’ve read the night before, and usually write some thoughts down in my journal. I’m finding the courage, overcoming the fear, giving myself permission, and learning to “excavate the truth” as Elissa writes. And for that I am grateful. 💚

Wow, your writing this morning was impactful and felt so familiar... thank you for sharing your thoughts and this book. I,too, along with so many others I’m sure, share a similar road with you. I think we are all trying to figure out our path and the best way home. ❤️

the confusion of "pride and shame" mixing together is well noted here as just one of the challenges i could easily imagine. To write beyond the influence of real or imagined "voices" their judgements or even needs is perhaps the biggest challenge to finding the truth in ones experience and yours is an interesting one and not adverse to the hard work.