It was cocktail hour on a sultry Saturday night in the City of Washington, 1964. Outside in the shady backyard, the air was thick with gnats and the sweet smell of my father’s gardenias. We were all there, I guess. Maybe not my sister, who might have noticed me go. I saw they were drinking bourbon. I knew that word, bur-ben, just like I knew nap tyme and dog-ee. My mother was smoking a cigarette and laughing, so I made a break for it. I pushed the side gate open and slipped down the narrow brick-and-grass driveway we shared with the neighbors, past the boxwood hedge that our poodle Pepe peed on every day, and into the street.

My little legs galloped along, my smock dress billowing around me, my Stride Rite Mary Janes click-click-clicking the gravel. The freedom, the thrill – nothing else mattered.

I never heard my father’s voice because he did not yell for me. He ran like hell, fueled on the adrenalin of fear, and scooped me up from behind with his strong arms.

“I couldn’t shout at you,” he told me many times years later. “Because there was a car coming down the street that I could see but you couldn’t, and I was afraid you would turn and run towards me and out in front of the car. I ran, wildly waving my arms at the car, and made it to you just before you would have darted around a parked car and into the middle of the road.”

I remember riding in my father’s arms back to the house, but nothing more than that. He still has a horridly vivid memory of thinking he was going to witness his toddler daughter get crushed by a car. He also remembers fixing the gate latch.

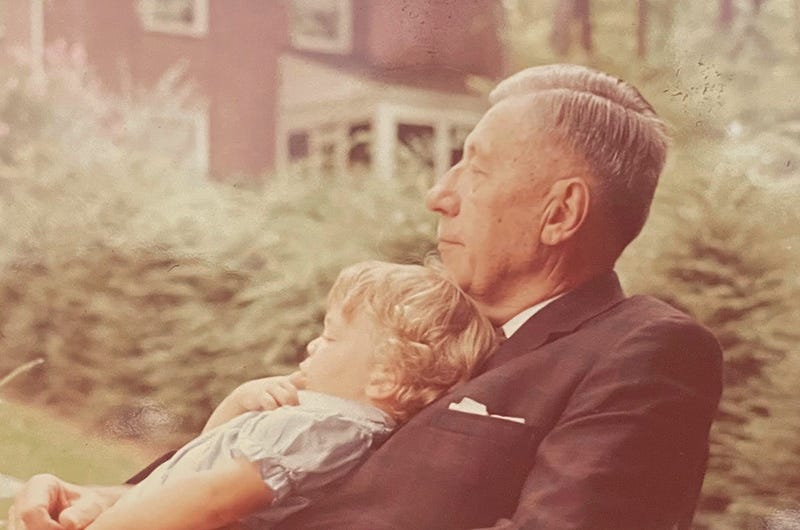

It’s not like I didn’t enjoy cocktail hour. Especially when my grandfather was over. Bum Bum was a big man, six-two. He smoked a pipe and had scratchy whiskers, and for some reason, I would sit still if he plunked me on his lap. We used to play a game where he would put one of his giant hands down, I would put one of my tiny hands on top of his, then he would put his other hand on top of mine and I would put my other hand on top of his. Then he would move his bottom hand to the top of the pile and I would move my bottom hand to the top of the pile, and then the hands would move faster and faster, slapping on top of each other, until the pile fell apart and I was in giggles.

Bum Bum was that to me, while he was Dr. Paul Putzki, chief surgeon of three hospitals in Washington, to the rest of the world. And a man who had just tragically lost his wife, my Nana. He came over to spend time with my parents and his granddaughters for solace and company.

So I don’t really know why I ran that day. Or why I ran all those other days. I just know I kept moving, was always moving. And to this day, I still have trouble being still, doing nothing, simply being. I know that’s all kinds of problematic. But I’m beginning to understand that sometimes I rely on my feet to move me to a better place when my head can’t get me there. I suspect my feet might know something my brain doesn’t.

Yesterday, I took a picture of my feet on the bike path in the State Forest, as I found myself out there just before dusk, desperately needing air and movement and pine needles and golden dappled light. “Look,” I thought, “You’re here. How did you get here? You followed your feet.” I was pretty down this week, nearly frozen in place at times, and yet, there I was, somehow doing the thing I needed to do.

This morning, I found myself in the garden. I tried to stay away, stay inside and do my work, but my feet took me out there and my clippers came with me. I thought I’d triage the zinnias and take inside anything lively looking. But instead, I found myself poking around for seedpods. I’d forgotten I let a whole head of lettuce go to seed, and there, swaying in the wind at the top of three-foot stalks, were hundreds of tiny treasure chests. I found spiky coneflower seeds and tufted cosmos seeds and needle-thin tithonia seeds. Nasturtium pods and dill seeds and calendula seeds – all manner of seeds clothed in crispy brown pods resembling miniature space creatures.

Later, I found my feet on the deck with Farmer. I’d left the back door open so he (and the flies) could feel free to wander in and out. But he stayed glued to one spot in the sun. I stood next to him for a while.

I am at the point where I watch him like a hawk. I carry a paper towel around to wipe the intermittent spontaneous drool that leaks sidewise out of his mouth. (Sorry for the visual.) I follow him as he wobbles on the short walk he still insists on taking through the woods to the edge of the property. Inside, I move his most comfortable bed from one room to the other, since he doesn’t want to be far from his pack, nor us from him.

This afternoon, my feet took me for a walk at Quansoo Farm with my husband. Quansoo – one of the most beautiful, quiet, open, healing places on the Island. Walking there is like walking in a kind of heaven.

Wide-open fields dotted with twisted, windswept trees. Carpets of moss, canopies of grape vines and bittersweet. Pond views and shore birds.

When I came home, my feet took me to the hoop house to collect the tomatoes, which keep coming, and to bring a pumpkin up to the front step. I realize I don’t care if the deer eat the pumpkins. For as long as they last, they look cheery on the steps.

Again and again this week, my feet took me to the only places where I could be present in the moment, instead of flinging my mind into the unknown future.

I know my feet will take me to the vet on Tuesday, where we will talk to our trusted doctor about Farmer’s progressing condition.

And then I’m pretty sure my feet are going to drive me back to Delaware in the next week or two.

I guess my feet know where they want me to go, as James Taylor wrote. Maybe I should learn to trust them.

🥾

Love this Susie. Thanks for sharing. This perspective is so important in recovery as you well know—to have your head and your feet in the same place. This essay evokes the presence of doing exactly that—and noticing it.

Prayers for Farmer as you love him relentlessly. 🙏❤️

Beautiful essay, Susie, and lovely description of Quansoo—indeed a magical place. Sometimes it seems best to let the feet lead while the mind takes a backseat, that way it can’t talk the body out of going where it needs.