I am in the back seat of a grey Honda Civic, watching the cornfields and clouds go by.

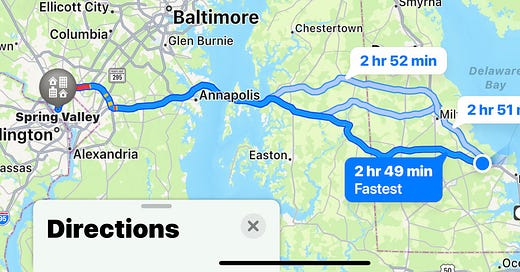

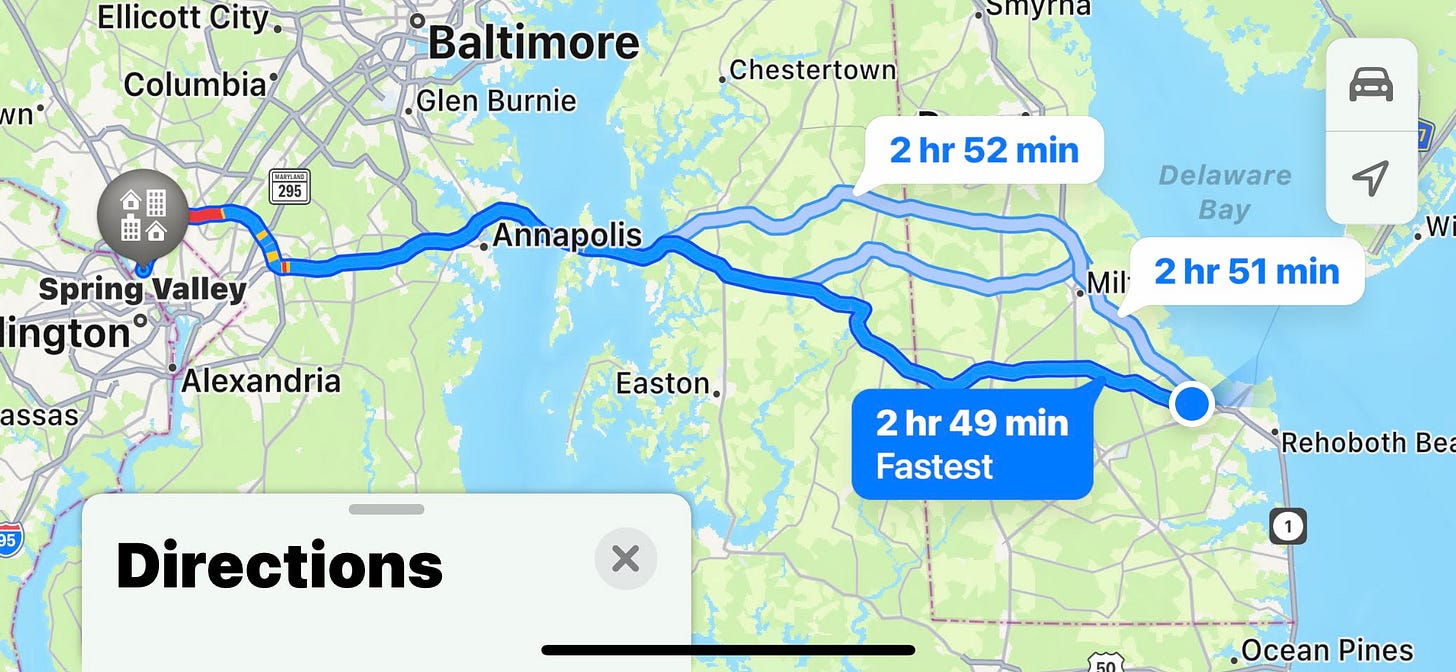

Our route, 121 miles from Milton, Delaware to Northwest Washington, is the “corn and soybeans” route, one we’ve driven, in some family form or another, for going on seven decades. Things have changed, things have not. The cows still lie down when the rain is coming.

Today the sky is September blue, with samples of Benjamin Moore Linen White brushed randomly on the ceiling.

Splash! One of those giant irrigation sprinklers on wheels sprays the car as we skirt Milford on Route 14. A country carwash.

All that corn and those soybeans are grown for chicken feed. Sussex County, Delaware, is home to more broiler chickens than any other county in the U.S. Little known fact.

Dad, 93, is in the front passenger seat, doling out directions to my husband, who is at the wheel of Dad’s leased car, which will soon be returned to the dealership for good.

We are taking Dad to a dentist appointment, back in the city where I grew up, where he spent his adult working life, and from where he and my mother could never fully detach, even though a retirement in Delaware, my father’s home state, always made sense.

Dad still has one foot in Washington and has been reluctant to give up his doctors. He has stubbornly driven back and forth from Delaware to Washington for the last five years. Until now, when my sister and I have awkwardly insisted that he stop doing this drive.

It is a strain, this role reversal with my father. When my Dad pushes back, my sister shuts down. And I go the opposite direction, my innate desire to control everything (hello alcoholism, hello daughter of a daughter of an acute alcoholic) kicking in. I try to “make” Dad do things, and it never works.

Today, for the car ride, I’ve turned my Dad over to my husband, who doesn’t have the history to deal with. They like each other, this husband and this father. And I’m grateful for that. And it’s nice for Dad to have another man to talk with instead of just his bossy (but loving) daughters.

As we head towards the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, which we will cross twice today, I realize I am relishing my fly-on-the-wall status and this gift of a day – a weekday no less – when I have almost nothing I am supposed to be doing other than showing up. I can’t do any work in the car, I’m not driving, and the roadway noise means it is difficult for me to engage in conversation with the front seat unless I lean way forward and insert myself. So I sit back with my magazine and listen with one ear. It is lovely.

Dad talks backwards in years – now he is reliving what it was like before the bridges were built over the bay. To get back to the Delmarva peninsula from Washington, D.C., he and his parents and brothers would take a small ferry from a remote landing at the end of a two-lane road near the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

This was the early 1940s, when my grandfather, a former naval officer, was making trips to D.C. to lobby his Naval Academy classmates to recommission him. With the war coming and the old-boy network working, he was successful. His years out of the navy had begun with a respectable engineering job with Babcock and Wilcox in Kansas City. But after being laid off during the Depression and returning to his hometown of Lewes, Delaware, to try and build houses and boats to make a living, the economics had become stifling, especially with six boys plus in-laws under his roof.

I let the conversation drift away from me as we slow down to cross the railroad tracks and avoid the speed traps of another small town. I chuckle when I see the railroad crossing sign – it reminds me of the Travel Bingo game my sister and I used to play in the car. It was one way my parents tried to keep us from disrupting the trip. We used to fall into giggling fits, my sister relentlessly tickling me, while my Dad got increasingly frustrated with us. “Settle down, girls!” he’d command.

Those cardboard Travel Bingo games got pretty tattered. And after a while, no fun. I think they were designed for family vacations to new and exciting destinations, not for a family that traveled the same roads, with the same road signs, back and forth, over and over. We knew where the only S-curve sign in Delaware was and where we were likely to spot the first horse or barn or church.

The magazine I’ve retrieved from my Vera Bradley tote bag is Better Homes & Gardens, now known as BHG. (Though in reality, it’s a reincarnation of Martha Stewart Living, edited by Martha’s former Design Director, Stephen Orr, who I begrudgingly admire, even though he and his team unceremoniously dismantled my alma mater, Fine Cooking magazine.)

I’m not a flipper of magazines, so I read BHG front to back. It’s an odd quirk, I know. Odder still: some part of me will always feel at home with a women’s magazine in my lap. I am not ashamed of this. I am the kind of person who likes to know that persimmon is the color of the year, that farmhouse modern style is still a thing, that there are 25 (more) things to do with puff pastry or biscuit dough, and that you should not, in fact, feed coffee grounds to your house plants.

I did not spring from the womb reading The New Yorker.

I did steal my sister’s Glamour and Seventeen magazines before I got my own subscriptions – and long before I took my first real job at Seventeen. For whatever reason, I will always associate magazines – the mashup of photos and words and art that I adore – with relaxation.

I realize I’ve let my eyes shut for a few minutes. We were up at 6 a.m. and as usual, I was awake reading way past midnight. Am I allowed to nap, I wonder? Of course.

The talk up front ranges from college basketball to the savings and loan industry, from taking the bar (they are/were both lawyers) to The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia (where they both visited as schoolchildren, my husband having grown up in Philadelphia). My dad talks about his brothers who were pilots (ship pilots) on the Delaware Bay, about his summers on the Menhaden fishing boats, about how my mother eventually learned to enjoy sailing with him.

And about how his Dad died. Young. 52. Essentially from adhesions from a botched appendectomy performed by an ER doctor who had been trained in obstetrics and basically performed a caesarean on him.

My grandfather was a smoker (and a drinker, though curiously not heavily until he turned 40) and coughed his stitches open, causing adhesions to form, which worsened over time. He was later operated on in Panama, where he was stationed and living with my grandmother and my Dad’s two youngest brothers. (A friend of the family had arranged for my father to go to boarding school on scholarship.)

That operation didn’t fix anything, and subsequently my grandfather died after another operation at the Naval Hospital in Philadelphia in 1948, six years after his son Jack – my dad’s oldest brother – was lost at sea when the merchant ship he was aboard was bombed during the infamous Murmansk Run during World War II.

Dad has outlived his entire family, not just in present time, but in actual years lived.

We make our way off the Beltway, through Chevy Chase, and down Massachusetts Avenue (retracing the childhood I showed to my husband back in March) to my father’s dentist, where we leave him for an hour while we get a jolt of city stimulation in a busy coffee shop.

Retrieving him, we walk to where the car is parked and Dad is winded. So winded that we have to stop three times for him to catch his breath. In my head I am furious at the cardiologist who postponed Dad’s latest appointment with him for another three weeks. I swear I will call their office when I return. But I know Dad doesn’t want me to. It is hard to know when to take a back seat and when to press forward. But it’s also increasingly clear that older people need advocates, as they are frequently short-changed.

On the trip back, my husband listens to more stories, some different, some versions of the same. I clandestinely take notes in the back seat. I have recorded my Dad a little, but there is so much more I would like to capture. I can’t hear everything – Dad’s voice is hoarse and raggedy these days – but enough to know what to ask him later. Around the dinner table, where there are no front or back seats, only a circle of family.

P.S. The next day, Dad spent four hours in the garden and did just fine. It is like this now – one day I am beside myself with worry about him, the next I am marveling at how this 93-year-old can do as much as he does.

Oh Suze!!! This might be my favorite..or 5 BEST pieces yve ever done!!! In my estimate!! I feel as though I’m there with U!!! I can’t wait for your book!!!🥰🌻♥️🌻🥰

This is the first piece of yours I have read, and I’m hooked! Sounds like you are navigating the role of daughter to an elderly parent quite well. I know from experience it’s not easy, and as I get older, I try to remember what it’s like to be the child in the relationship. Thank you for the memory of Seventeen magazine; I would ride my bike to the grocery store to buy the latest copy. I miss magazines, as well as newspapers. I still subscribe to one magazine, although it’s not the same. But then again, neither am I after experiencing the internet.